Reviewing The Last Mistress from Ideology

Catherine Breillat has largely been viewed by film critics as a controversial French Director, after a series of lascivious experiments with mostly audience-bludgeoning, totally anti-romance films like Romance and Fat Girl. But in The Last Mistress, she unexpectedly stepped out of this tradition and produced a lurid exploration into the passionate and lustful side of male-female relationships. Catherine Breillat’s The Last Mistress has helped the female director to preserve her singular feminist roots, merge her psychosexual explorations in the imbalances of men and women, and still assemble her most reputable art house film. Directed and written by Catherine Breillat, the Jean-François Lepetit film, intones ideologies of sex, of lust, of domination, and of the French Aristocracy.

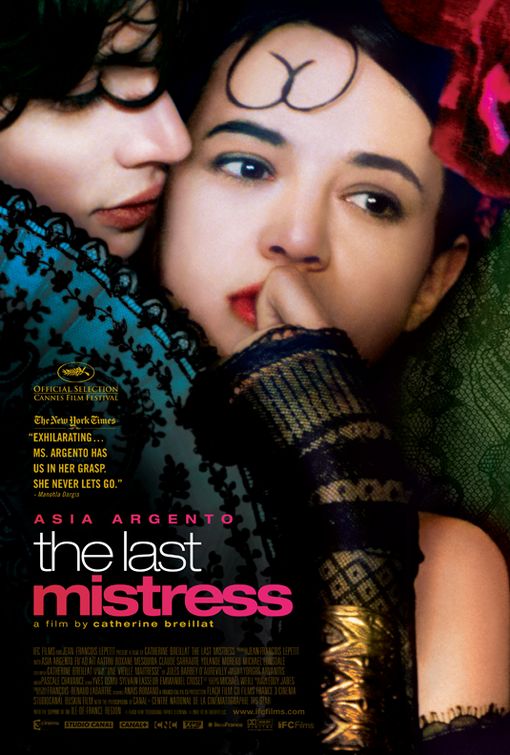

The engrossing film is based on Jules-Amedee Barbey d’Aurevilly’s novel ‘Un Vieille Maitresse’ written in the 19th-century. The storyline of the film is basically about a tale of love, lust and deceit. A 30 year-old French libertine attempts to cheat on his betrothed, every inch a chaste aristocrat, so that he can marry the beautiful daughter of a famed Italian cum Spanish nobility. This helps introduce the Andalusian courtesan, a ferocious lustful character, and a venomous Madame, in the name of Vellini (Asia Argento). Vellini is a flamboyant young blood, with hair to match her fiery spirit and an attitude that scorches the very earth she walks on.

The young playboy by the name Ryno de Marigny (Fu’ad Ait Aattou) dismisses the married woman at first calling her an ‘ugly mutt’ only to change after a moments stare. He resolves to domesticate the daughter and wife of nobility despite her hatred against him. Through flashbacks, we learn how Ryno’s initial loathing for the perfect mistress to be, Vellini, turned into arousal, then pursuance and finally conquest. Indeed, eventually, he manages to pull her into exile in Argentina where they sire a daughter. The daughter however dies soon after, following a scorpion sting. The loss throws the couple, especially Vellini, into a grief abyss, with desperate bellowing growls. After the loss, the couple realizes they are not in love, and resolve to live as a man and mistress thereafter.

This could have been a costume drama but Catherine Breillat spins an erotic in-depth account of romance powered by pure desire and lust. The large part of the film is played in flash backs, based on Ryno’s confession to La Marquise de Flers, about the ten years affair with Vellini. La Marquise coincidentally happens to be a grandmother of Hermangarde, Ryno’s wife to be. This helps cast a lurid picture of a passive cruelty that becomes after a relationship is left passionless. As Ryno narrates about the affair with Vellini, it is clear to all that he is sold to her for good. Vellini is a carnal beast, terrifying and dominating, but also alluring and sensual.

Breillat chose not to critic love traditions and ideologies, but rather the natural addiction to lust, or what Ryno calls, insatiable wanting. As Vellini follows Hermangarde and Ryno to a seaside recluse, it is only to confirm that if Ryno still wanted her instead of Hermangarde. The perfect mistress, Vellini, has a piecing sexy voice that thrills any man. As Vellini and Ryno become enemies, then unknown attractions, then lovers, then parents and then back again to the circle, the film exposes the sinister cat-and-mouse games men and women play for lust. Vellini easily tempts and lures Ryno from his virtuous wife, Hermangarde, with her knowing gaze and ardent sexuality. This is pretty much what happens in modern society’s affairs.

She knows how to look at a man and weaken his defense to the core. Her whispered taunting and chest thrusting movements that are most graceful awaken the groins of Ryno, as they do for those in the audience. Again, Catherine Breillat’s The Last Mistress indulges in some mussing sexual identities such as Vellini smoking a cigar, as Ryno daydreams in love, while Hermangarde elicits no sexual feelings in Ryno. Vellini easily dominates a milquetoast Ryno, in both intellectual and sexual prowess, despite Ryno’s attempt to be faithful to his plain-featured yet comely bride. Breillat would have been expected to cast an image to the opposite.

The Last Mistress is slightly perverse and bearing several soft-core porn shooting and lighting. It features a masterpiece theatre style laden with subtexts. Ideologically, the motive is to offer insights to the female sexuality in a comparative relation to contemporally religious constructs and practices of male supremacy. Catherine Breillat’s The Last Mistress scores hugely for successfully transferring Jules’ male-centric novel into a philosophical account of male-female relationships, spiced with a sly feminist critique.

Controversial sexual explorations are toned down, but still Breillat’s preoccupation is apparent especially with profane chicken slaughter, kooky sexual positions, wound licking and then the erotic asphyxia just next to a burning, charred corpse of a 3-year-old. Perversion is actually mostly used in art to symbolize a demonized female domination and sexuality. But Catherine Breillat may as well be intimating about the virulent cannibalistic nature of the 19th Century French socialites, which is the setting of the film. On the bottom line, the 114 running minutes of Catherine Breillat’s The Last Mistress, makes a clear implication that the male species is a simplistic creature that’s driven by sexual entitlement and impulse, while women usually employ manipulative biological drives and hard-earned wit to obtain denied power.